Value-based care is an approach to healthcare delivery that links the cost of care to the quality of care.

It is the opposite of fee-for-service healthcare, which rewards providers for doing “more” of what’s billable to payers and what yields the highest reimbursement levels, which may or may not yield the best outcomes.

It is also a method for changing the dynamics between patients and providers and between payers and providers. It emphasizes “doing” what is best for patients, what is rooted in evidence-based practice, and what engages patients in their health and healthcare interactions.

In this article, we will cover:

- Defining and Describing Value-Based Care

- A Glossary of Terms

- The Problem with Health Outcomes in the United States

- How Value-Based Care Can Improve Health Outcomes

- Value-Based Care Resources

I wrote this post to go with our podcast episode OT and Value-Based Care, so it was written with therapists in mind, but hope it will be helpful to anyone who finds it.

You can also sign up for Dana’s newsletter for more value-based care information.

Defining and Describing Value-Based Care

The simplest way to describe value-based care may be “quality over quantity.”

But, the term “value-based care” doesn’t always resonate with patients. It can even be confusing to healthcare providers. The United States of Care ran focus groups to better understand what language would help patients understand the mechanics of value-based care. Part of what they examined was what the public preferred for their health care. These four preferences stood out:

- Value-based over fee-for-service

- Provider accountability

- Reduced wait times

- A holistic care approach

The alternative terms that stood out most among other proposed options to replace value-based care were “quality-focused care” and “patient-first care.” While the United States of Care has compelling results of their work, changing the term value-based care has generally not been widely adopted.

But what is certain, and a big takeaway from their work, is that people want to receive care where the provider payment is tied to improved patient care and health outcomes rather than quantity. The latter yields fragmented, poorly coordinated care.

Glossary of Value-based Care Definitions/Terminology/Concepts

Value-based care makes big-picture sense, but it does require us to get learn some new terms and concepts. Here are some of the most important ones for you to learn, as you explore this exciting shift in health care.

| Term & Acronym | Definition | Example/ Context |

| Value-based care (VBC) | Healthcare delivery model where providers are paid based on patient health outcomes rather than service volume | Payment linked to reduced spend over the course of a period of time and maintaining or improving “quality.” Examples are: reduced hospital admissions and readmissions, reduction in unnecessary medical specialty care, reduction in unnecessary advanced imaging, improved early detection and treatment of illness. Improvement in quality metrics may include improvement in process metrics or outcomes metrics, and may start off as a “pay-for-reporting” structure. |

| Quality measures | Standardized metrics used to evaluate healthcare provider performance and patient outcomes. Performance on quality metrics will determine qualification for financial performance rewards | Patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs), HgBA1C control for diabetics, more days at home per year for patients with multiple chronic conditions, blood pressure control for patients with hypertension, etc. |

| Accountable care organization (ACO) | Groups of providers (physicians, hospitals, home health agencies, FQHCs, etc.) who make a formal agreement with a payer(s) to collaborate and coordinate on managing a population of patients | Patients are assigned to a physician or APP based on choice and/or historical claims. All providers accept responsibility for managing those patients in a patient-centered, high-quality way with the goal of reducing total cost of care across the care continuum while improving quality and the patient experience |

| Population health | Managing the health outcomes of a defined group of people and often includes reducing health inequities | Strategies to improve pop health include, for example, individual behavioral strategies, disease prevention and early detection strategies. Population health outcomes examples: increased life expectancy, decreased obesity rates, earlier detection and treatment of certain cancers. |

| PMPM | Per member per month; refers to the expected cost of managing the health and healthcare of a population month over month. It’s used in determining benchmarks and target spend over a calendar year with one payer | The amount per member per month is determined by the payer and is based on inputs and claims data on each person, commonly based on each individual’s prior year claims data and medical “risk adjustment” scores (prospective), after the end of the year (retrospective), or concurrent (during the year—this is the least common and used generally in carve-outs of the population, like ESRD patients and seriously ill beneficiaries). |

| Episodes of care | Models that hold providers accountable for cost and quality over a defined period of time. The time may be a fixed time, after a procedure, after an illness, for treatment of a specific disease, etc. | Sometimes these are defined as “bundled” payments, and other times they are defined as a disease specific model, like oncology care. In some programs, all providers who care for the patient in an episode are paid as they normally would be paid, and then the payer reconciles per-episode, per patient performance (cost and quality) after the episode and all claims are submitted. In that case, the provider who “took the risk” for the episode would either earn shared savings if they saved money and maintained or improved quality, or would owe the payer money if spend was higher than expected and/or quality worsened. In other cases, payment is made to one provider who is responsible for paying downstream claims to other providers. the “at risk” provider determines how to reward or “punish” other providers for performance. |

| Access to care | The ability to enter the healthcare system to receive needed health services of any kind. Includes affordability, availability, being able to physically or technologically reach care | One of the barriers to optimal health outcomes is lack of access to care. Without access, individuals often don’t receive care until it’s an emergency. In some areas, there isn’t sufficient available care. In some cases, there’s available care, but some individuals can’t access it. Expanding access is a driver of value in healthcare and health outcomes. |

| Primary care models | Alternative payment models designed for primary care provider participation. | Medicare has had several. Comprehensive Primary Care (CPC), then CPC+, and now Primary Care First, and just started = Making Care Primary. All of these are Innovation Center Models. This is only a partial list. |

| Care coordination | Organizing care and care activities across providers. Important for delivering safe, patient-centered and evidence-based care. Essential for optimizing outcomes, especially in those with multiple conditions. | Coordinating medication and treatment choices for a condition that’s being managed by more than one provider, avoiding duplication and confusion, sharing information about progress, etc. Primary care providers are often the quarterbacks of their patients’ care but in FFS, there is no incentive to share information back from specialist to PCP. |

| Capitation | Paying providers a set amount per month, regardless of services actually rendered. | This takes many forms. The original capitation disincentivized patient visits. Capitation in the context of VBC is different. It can be a set monthly fee for services without billable codes or to provide any of a handful of services, but those services must be provided. It can be a monthly payment per patient that exceeds historical spend to fund team-based, advanced primary care activities and make it more likely the practice will help patients avoid high-cost spend. In VBC, payment is always linked to quality metrics. |

| Health information exchange | AKA “HIE,” is a system, often statewide, that allows for securely sharing and accessing a patient’s medical information. It is regulated by the the Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy (ASTP)/formerly Office of National Coordinator (ONC). It involves sharing information in a timely way. | The goal of HIEs is to improve the speed, quality, safety, and cost of patient care. It isn’t a substitute for care coordination, but is critical for timely information sharing to facilitate the right care at the right time in the right place and improves the completeness of patient records. Blind spots in care across the continuum and over the course of the year are barriers to high-quality, patient-centered care. |

| Patient engagement | Active patient involvement in their own care and in successful management of chronic conditions. It’s also important in preventive care and early identification of diseases. | Americans are used to seeking care in reaction to illness or injury. And it’s common in chronically ill patients, especially when the illness is at least partially related to lifestyle/behaviors, not to comply with or even fully understand how to manage their conditions and when to seek help before it’s emergent. An engaged population of patients sees their PCPs as their medical and healthcare “home,” and has a good relationship with their care teams. For patients with chronic illness, strong patient engagement increases the chances they will work with care teams to manage their conditions and reach out proactively when they have questions or problems. |

| Clinical pathways | Standardized, evidence-based care plans that outline the best practices for managing specific conditions. | This is particularly important for highly-variable care, either by condition or by particular specialists of the same kind being involved in a patient’s care. They support the activities of team-based care professionals like registered nurses, who are often the ones helping patients carry out their care plans |

| Health equity | It’s a term used when everyone can attain their full potential for health and well-being, regardless of other inequities like disability, demographics, health literacy. | It’s determined by the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, play, and age. In VBC programs, health inequities influenced by modifiable factors are opportunities to intervene and address non-medical drivers of health. There is no mechanism for doing this in FFS and no incentive, either. |

| Chronic care management | Services that help patient manage their chronic conditions more effectively. CCM is a billable service, added to the physician fee schedule in 2015. | May be provided by clinical staff in a care team, but must be billed by a physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, clinical nurse specialist, or certified nurse midwife only. In ACOs, it is commonly provided by nurses. CCM services are usually not face-to-face. |

| Risk adjustment | Methodology for determining payments by payers that’s specific to the risk of the population. “Risk” is determined by specific diagnoses that have been linked to a higher risk of spending. | In VBC programs, every patient is assigned a “risk adjustment factor” comprised of the total score of medical diagnoses determined by the payer to “map” to potential spending. The highest are for end stage diseases. It’s crucial that participants see their patients annually to determine their “risk.” Only some diagnoses have an associated risk, or “hierarchical condition category.” Some ICD.10s have them and some don’t. Some are for just acute issues, but most are for chronic and persistent conditions. The per member per month dollar amount associated with each patient is determined by their risk adjustment factor, or “RAF.” |

| Participating provider | Common term for a provider in a contract to participate in a VBC program with a payer. | In the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), all the physicians and advanced practice providers in each TIN are the participating providers. |

| Patient attribution | The method used in a VBC program to determine which patients the participating providers are responsible for. This is commonly done through claims, and some programs allow voluntary attribution to a provider. | The attributed patients will each have their own RAF (see “risk adjustment”). If a patient’s conditions weren’t captured, they won’t have a RAF associated with medical conditions. Only their demographics will contribute to their weight for contributing to a program’s per beneficiary per month benchmark. It was developed to avoid “cherry picking” patients in Medicare Advantage. |

The Problems with Health Outcomes in the United States

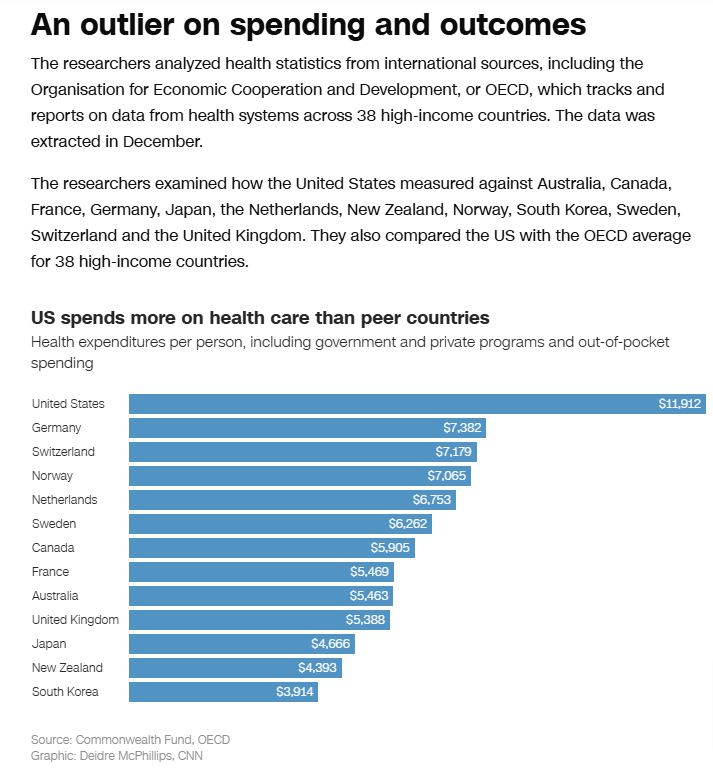

Americans pay more for their care than any other country. They spend nearly 18% of GDP on healthcare, but die younger and are less healthy than those in other high-income countries.

Unfortunately, they also have the worse health outcomes among high-income countries.

The U.S. also has the highest rates of avoidable deaths among high-income countries. This refers to deaths that are preventable and treatable. That can be through public health measures, primary prevention like diet and exercise, timely interventions that are the result of regular exams, screening, and early treatment.

From CNN.com:

Here’s the Commonwealth Fund’s graphic showing the percent of GDP spend on healthcare from 1980-2021 of OECD countries:

Here’s the Commonwealth Fund’s graphic showing U.S. life expectancy at birth compared to the OECD average:

We have the highest rates of assault, the highest rate of people with multiple chronic health conditions, and the highest obesity rates. Our life expectancy in 2022 was 77.43 years old, which is three years less than the OECD average.

United Kingdom’s life expectancy: 82.06 years

Canada’s life expectancy: 81.30 years

Infant and Maternal Deaths in the U.S. are the highest of all OECD nations:

In short: Americans don’t get much for what they pay for care, if outcomes are used as the barometer.

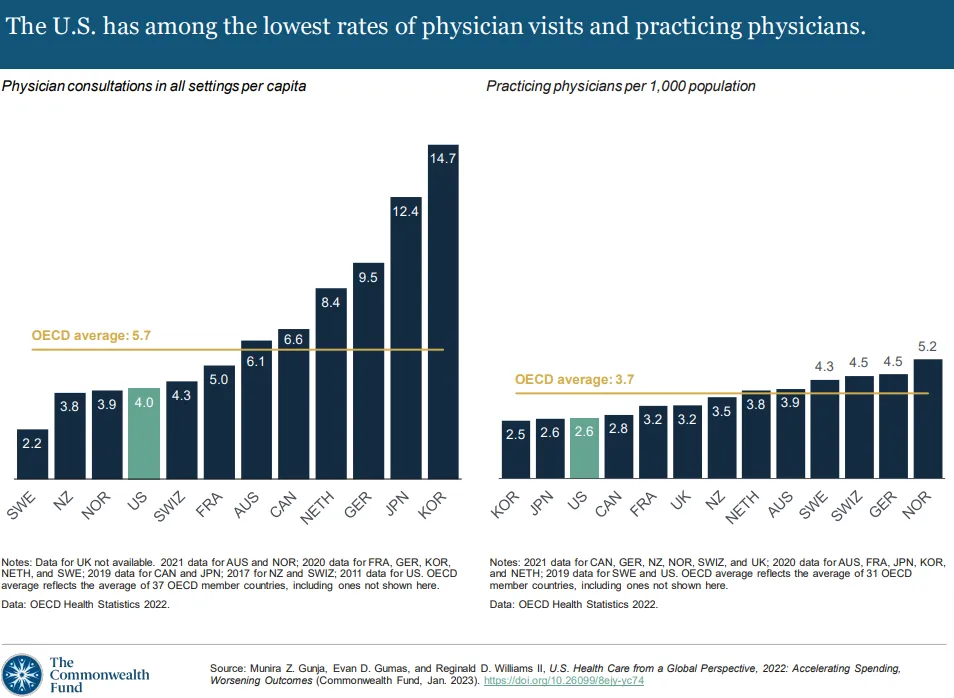

Low Rates of Physician Visits and Practicing Physicians

America has low rates of physician visits and low numbers of practicing physicians. To make matters worse, around 20 percent of practicing physicians are aged 65 and older. There is a continuing physician shortage, harming patient access to preventive, upstream care. To then add salt to the wound, people aged 65 and up, who need more healthcare overall than those under 65, is expected to move from 17% of the population in 2024 to 23 percent of the population in 2050.

The shortage has dire consequences for a country dependent on physicians for most upstream care.

Why is there such a shortage?

There’ no “one” factor, but here are some major contributors:

- Time, expense, and availability of medical school training (supply and demand)

- Insufficient graduate medical education (GME)

- High burnout rates (which also lead to worse outcomes)

- High rates of chronic conditions in America and unmet social needs impacting health, with no incentive in our fee-for-service system to address managing them. More seek care and support more often, increasing demand

- Increased access to health insurance since the Affordable Care Act, increasing demand

As reported here by McKinsey, physicians are approached regularly about other job opportunities. Half of those who responded to their survey reported being approached weekly.

Physicians also believe their time is not optimized for patient care and that they should be delegating a significant amount of work to other clinical and non-clinical staff.

Of the care that they believe can be delegated, advanced practice professionals, nurses, and other clinicians should be delegated to more than anyone or any other solution.

How Value-Base Care Can Improve Health Care

There is clearly much room for improvement in our current health system.

How Value Based Care Delivers What Patients Want

Patients want personalized care. They want providers to engage them and their care partners in shared decision-making. They want their providers to have the time and flexibility to address their needs, to understand them, and to make sure their preferences are understood. They want providers to understand their goals for their health and for their healthcare and to partner with them to help achieve those goals. They also want to understand their healthcare and their options, regardless of their level of health literacy.

When seeking healthcare, people prioritize affordability, access, and a positive experience. Barriers to any of these will limit the right care at the right time with the right provider at the right site of care.

Physicians’ Role in Value-Based Care and Team-Based Primary Care

Primary care physicians, in particular, are leading in value-based care. Why?

Value-based care participation provides flexibility and higher funding levels (especially in the advanced alternative payment models—more than nominal downside financial risk), allowing primary care providers to build out teams of care. It also allows them to spend more time with patients, outreach to patients proactively, and improve access to care they can offer to their patients. It also helps reduce burnout.

Physicians also often add new clinical team members to enhance primary care delivery. Common additions to the care teams are advanced practice providers (APNs and PAs), behavioral health providers, registered nurses, clinical pharmacists, and dieticians.

In this article in the American Journal of Managed Care, this quote is pertinent to non-physician providers:

Future research may benefit from formal assessments of how the combination of these care team enhancements affects physician time expenditure, physician experience, and how diverse clinical team members spend their time.

Takeaway:

More value-based care incentivizes team-based care, and the right combination of healthcare professionals on primary care teams may ease the burden of the physician shortage while providing more of the right care at the right time in the right place.

It may also reduce burnout that leads to clinical attrition of physicians, and it can reduce the need for some of the specialty physician care that is often a relief of the bottleneck in fee-for-service.

A Health System Challenge to Reduced Specialty Physician Referrals

I noted above that team-based primary care can lead to reduced specialty care utilization. A primary care team of clinicians who can provide the right care, often more conservative, will prevent unnecessary, avoidable, and costly visits to specialists.

For health systems who have purchased medical practices, their incentive to enter into risk-based, primary care value-based care models is diluted if it yields reduced utilization of the specialty practices they also own. Because of this, it’s a challenge to incentivize health system-owned primary care practices to enter into value-based care contracts with strong incentives to reduce specialty care utilization.

This can only be addressed through policymaking. Health systems purchased medical practices to address “leakage,” but also because those practices bill a higher rate because of their hospital ownership. This lack of site neutral payment policy has incentivized even more high-cost, highly-variable medical specialty spend.

How Value-Based Care will Incentivize Evidence-Based Practice

There’s good news for providers whose services are of the highest value to individuals and to the cost burden on us all (think OTs, PTs, mental health professionals, etc.) but who have natural and cultural barriers to patient access. The value of these professionals is much greater than the reimbursement that’s been determined by the American Medical Association/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee (RUC).

Background on the RUC

In 1992, Medicare changed how they pay physicians and other healthcare professionals. It’s now based on the resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS). The values of all “medical care” are actually determined by physicians and medical specialists. Relative Value Units (RVUs) are specific to each service by each provider type, and are made up of several components (work expense, practice expense, and liability expense), and they are then adjusted by geography before being multiplied by the conversion factor. So if they RUC determines a certain provider’s specific service (designated by CPT/HCPCS code and the actual provider rendering the service) is worth X amount, that’s what’s multiplied by the conversion factor (Medicare or other payer’s).

In fee-for-service, you earn more by accumulating more and higher-reimbursed RVUs. But in value-based care, you are paid for the results of the care you deliver. Payment levels and opportunities are determined by the type and risk level of the program for each payer. In a full-risk, population-based program, where good annual patient outcomes can drastically reduce “expected” payer spend, the difference between “expected” and “actual” spend can be significant. In full-risk, most of that difference is given to the providers as a reward.

Think about a patient who is at high risk of falls. In a full-risk arrangement (where greater flexibility about how care is delivered is also part of the contract), a home visit where an OT addresses fall hazards, bathroom safety, and other risks may prevent a fall with serious injury. Overall, the spend for that visit is negligible.

Why? Because preventing that potential spinal or hip fracture, very common and very high-cost, can conservatively save the payer $75,000 in preventing the hospital stay, surgical fees, post-acute care, readmissions, subsequent complications, etc.

The value of services by the OT just went up exponentially.

That’s the power of value-based care, and it can be harnessed when you understand how the programs work and the funds flow.

Value-Based Care Resources and References

There is so much to learn about value-based care. Here are some recommended resources so you can continue your learning.

| Name | Description | Time |

| FFS Healthcare is Making us Sick | Makes the case that VBC is better for all stakeholders | 3 min. |

| Advanced Primary Care Interactions | Advanced primary care physician, patient, and care partner describe the impact of the integrated care team on managing his chronic condition | 2 min. |

| CMS: Value-Based Care Basics | CMS’ description of VBC as a foundational concept. Links out to additional resources | 2 min. |

| NAACOS’ Intro to ACOs video | The National Association of Accountable Care Organizations is the trade association for ACOs. The ACO is the most common type of value-based care model | 5 min. |

| Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC) | PTAC’s reference guide to common alternative payment model approaches. PTAC was created by MACRA. Physician-focused payment models are a type of alternative payment model | 10 min. |

| Alliance for Health Policy (AHP) Health Policy Handbook | Handbook developed by the Alliance for Health Policy with support from Health Affairs and Arnold Ventures. It is an introductory resource on health policy and the health care ecosystem | 60-90 min. |

| National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: High-Quality Primary Care | Consensus Study Report published in 2021 by the National Academies Press. Covers what happens when high-quality primary care is not the center of the health care ecosystem | Full book length |

| Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network (HCP-LAN) | Public-private partnership committed to advancing alternative payment model adoption across payers and providers. | n/a |

| Triple Aim to Quadruple Aim | We used to call it the “Triple Aim,” or the “North Star” for improving healthcare, which included enhancing the patient experience, improving population health, and reducing costs. The fourth goal is improving the work life of health care providers, including clinicians and staff | 10 min. |

| Quadruple Aim to Quintuple Aim | This adds a fifth aim for healthcare improvement—advancing health equity | 5 min. |

| US of Care’s Patient-First Care” Principles | Details four major areas of focus to guide the transition towards patient-first (value-based) care | 5 min. |

| Health Equity: WHO | See graphic inside, also found via the link | 10 min. |

| United States Preventive Services Task Force | Experts in disease prevention and evidence-based medicine provide services for the USPSTF. They make evidence-based recommendations about clinical preventive services. When they make an A or B recommendation, those may be added to the CMS list of preventive services provided without a copay in Medicare (linked inside this page) | n/a |

| Duke Margolis Institute for Health Policy: Select key resources | Prominent health policy institute | n/a |

| Timeless Autonomy | Health policy newsletter for HCPs written by Dana Strauss |

Conclusion

Value-based care is a win-win-win.

It is a win for patients—because they get right care at the right time.

It is win for providers—because they are incentivized to provide quality care over volume, and then get paid for the quality they deliver.

And, it is a win for payers—again, because when the right care is delivered at the right time it saves money.

I hope this post has left you excited for this new reality. Please, let me know any questions in the comments.

And, for more up-to-date information, you can sign up for Dana’s “Timeless Autonomy” newsletter here.