Occupational therapy practitioners turn to evidence-based practice (EBP) to look for answers, treatment recommendations, and affirmation that we’re truly providing the best possible care to our clients.

Once you start immersing yourself in the world of EBP, you will quickly find that there are several ways of conceptualizing the levels of evidence—and, depending on your purpose and setting, you might find a certain model to be the most helpful.

In this article, we will explore why the levels of evidence matter in occupational therapy. We’ll also cover some standard ways of looking at levels of evidence— and we’ll take a look at the evidence pyramid I’ve been using for my journal club, which has been helpful for me in looking at OT-specific research.

Why levels of evidence matters for OTs

Let’s discuss “levels of evidence” and how they apply to evidence based practice in OT and knowledge translation.

Research evidence is a critical part of EBP, but there are certain presentations of evidence that are more helpful to your clinical practice than others.

The levels of evidence serve as a mind map for conceiving which methodologies are most stringent and sound, and which ones should impact your practice most.

For example, an intervention is more evidence-based if a systematic review has indicated its efficacy, as opposed to that same intervention being supported by 100 promising case reports.

What are the different levels of evidence?

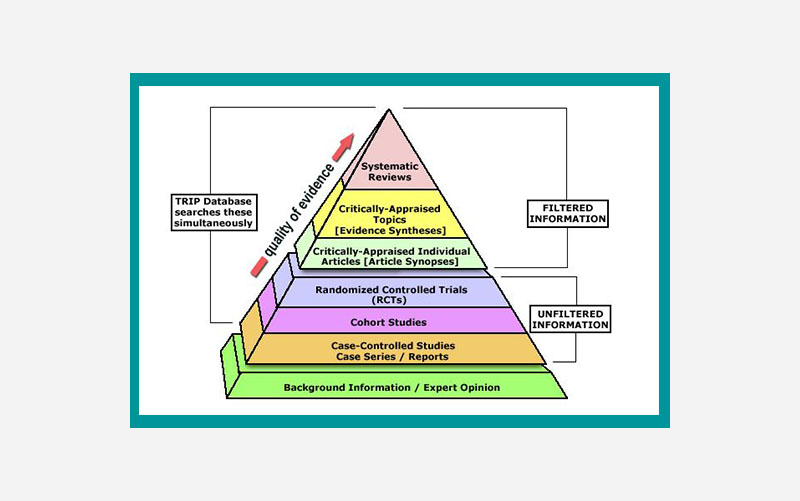

When searching for evidence-based information, you should generally select the highest level of evidence possible.

These are systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and/or critically-appraised topics. These sources of information have all gone through an evaluation process, and are considered “filtered.”

Research articles that have not been evaluated for validity or efficacy are considered “unfiltered.” The categorizations below are adapted from the 2017 book, Kielhofner’s Research in Occupational Therapy.

Disclaimer: Keep in mind that the “levels of evidence” system isn’t foolproof. A quality design (even a systematic review!) could be poorly executed and misleading, just as an obscure case study may actually align most closely with your particular patient—and therefore be the most helpful to you. It is also important note that a lower-level study in a prestigious OT-related journal may carry more weight than a systematic review in an obscure journal.

That said, let’s look at the levels of evidence. And, by levels of evidence, I mean essentially, the degree to which you can trust the research article, based on study design:

Filtered information (syntheses of previous studies)

Level I (Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses)

A systematic review is a structured review of all of the relevant literature on a topic. It is performed by searching for relevant articles, analyzing them for their validity and efficacy, and summarizing all of the literature results for a specific topic.

A meta-analysis is a systematic review that uses statistical methods to combine numerical results from many studies to summarize results. To help practitioners, the Cochrane Collaboration has its own database that contains even more helpful systematic reviews. The Cochrane Collaboration are experts in systematic reviews, and have even included their own level of rigor to help determine the efficacy of a treatment intervention. See what determinations the Cochrane Collaboration has stated about your favorite treatment intervention (if they examined it): Cochrane Collaboration

Level II (Critically Appraised Topics)

These are abbreviated versions of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. They are brief summaries of the best available evidence.

Unfiltered information (the studies themselves)

Level III (Randomized Controlled Trials)

In randomized controlled trials (RCTs), participants are randomly allocated to either an intervention group or a control group, and outcomes of both groups are compared. A double blind randomized control trial with a large number of participants has the strongest support for a “cause-and-effect” relationship with an intervention and the participants. (“Double blind” means all participants in both the intervention and control groups are “blind” to which group they’re in—and the administrators of the study are also “blind” to who is in each group.)

Level IV (Cohort Studies)

A cohort study (also called a longitudinal study) involves participants being assigned to a treatment or a control group. The assignment is not randomized. The study follows the groups of participants throughout a duration of time and gathers results. These studies are often not blind studies, and it is very difficult to control external variables that might impact the results.

Level V (Case-Control Studies and Case Series Reports)

A case-control study compares patients who have the outcome of interest (e.g., a disease) with patients who do not have the same outcome/control (in this example, a disease), and looks back retrospectively to examine the relationship between a particular variable (e.g., risk factor) and the outcome/control/disease. A more detailed example: comparing lifeguards who have developed skin cancer to lifeguards who do not have skin cancer and asking both groups the amount of sunscreen they wore.

These study designs are used during the early stages of research to help identify variables of interest. Case-control studies and case series reports often have a small number of participants, and are not generally randomized or controlled for confounding variables.

Level VI (Background Information and Expert Opinion)

Though every research project has a theoretical foundation, this study design on its own can be heavily influenced by personal beliefs and opinions. This evidence level is also deemed anecdotal evidence.

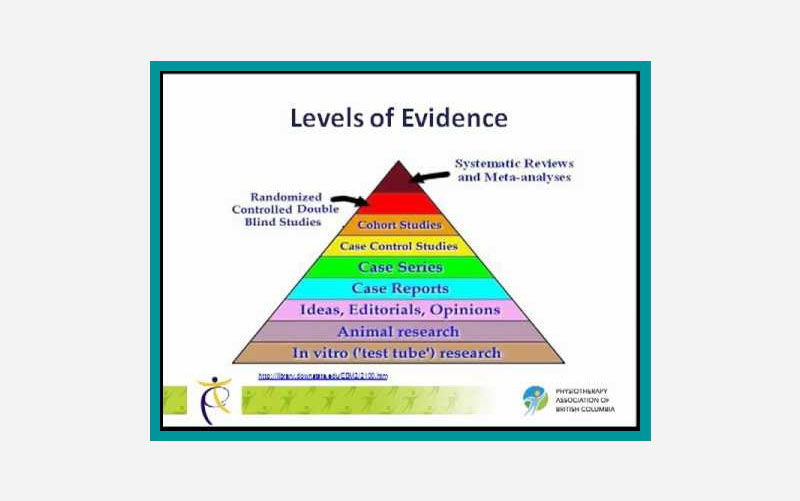

Common ways of organizing the levels of evidence

Now, if you were to Google levels of evidence, you might feel confused because there is not one standard evidence pyramid.

But, when you are looking at the various evidence pyramids out there, you should definitely see themes that you recognize (with systematic reviews being the highest quality of evidence, then RCTs, then case studies, etc.).

From there, there are nuanced differences in what is included and what is not included, based on the application of the pyramid.

For example, if you are focused on cutting-edge research as you try to bring a new technology to market, a pyramid that includes in-vitro and animal research would be really important to you, because this is where you will find cutting-edge advances happening.

Evidence pyramids that contain only research studies.

For us practitioners, though, the most important thing is probably having evidence filtered and explained regarding how it is applicable to our daily practice.

Most of us don’t have time to look at animal research and ponder what might come of it in 20 years. Therefore, a pyramid that highlights filtered information is probably the most helpful.

Research pyramids that divide evidence into filtered and unfiltered information

I also need to note that even though we tend to conceptualize levels of evidence in numerical form, there are also many examples of pyramids using numerical-alphabetical value. This is especially helpful for organizations who want to use a shorthand for the strength of evidence. For example, this treatment has level 1B studies, whereas this other one only has 3B level studies.

In fact, the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) Approved Provider Program uses a numerical-alphabetical hierarchy for assessing evidence used in their professional development activities.

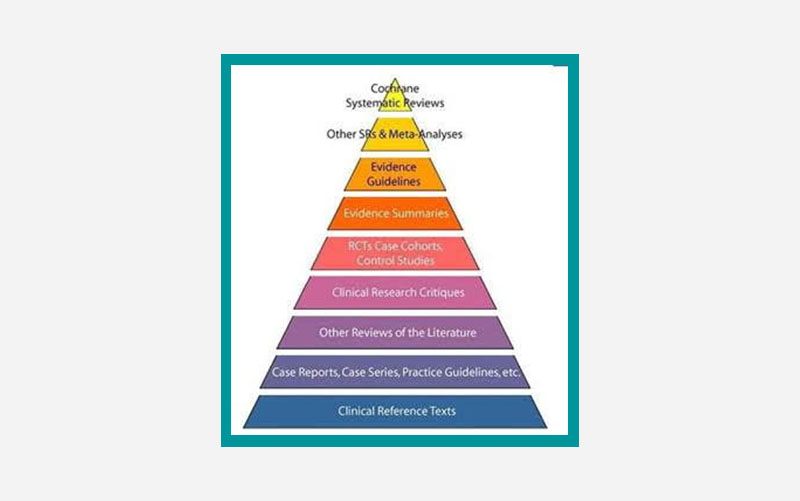

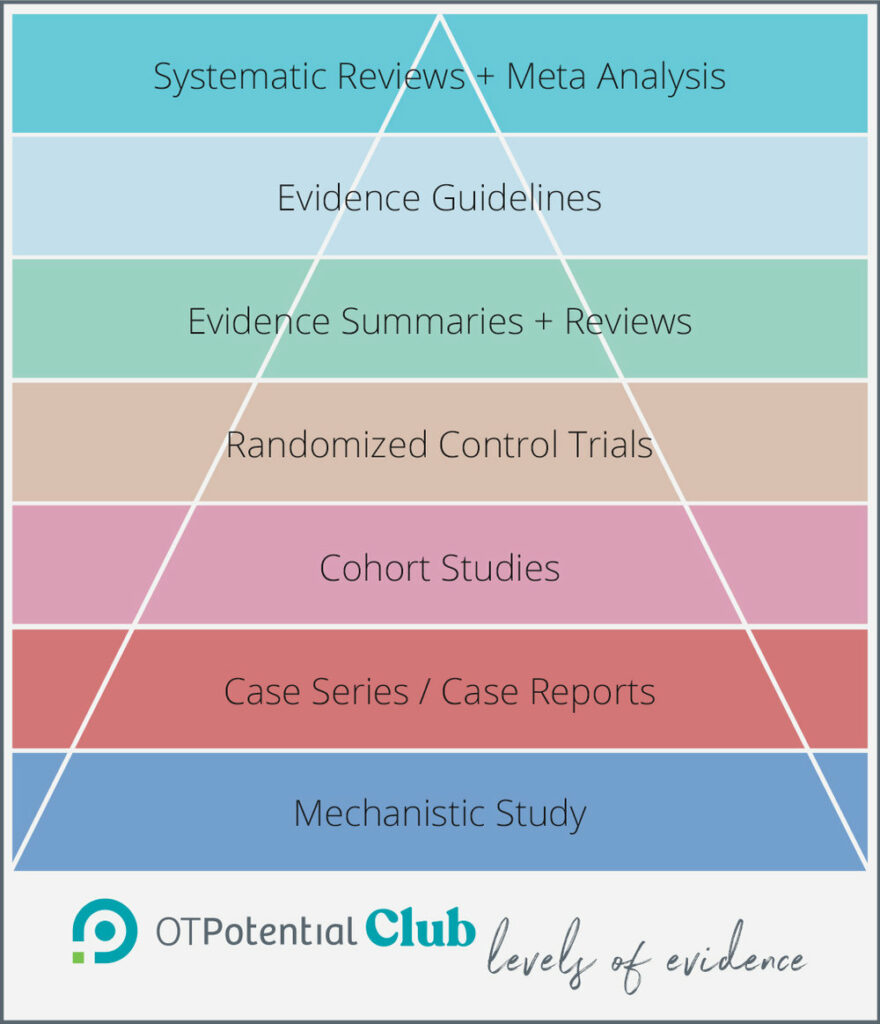

OT Potential Club levels of evidence pyramid

As I’ve been operating a journal club with weekly article reviews, I’ve started to hone in on a conceptual hierarchy of evidence for influential OT-related articles.

First, for practicing clinicians, articles that contain a synthesis of information seem to be the most helpful. The content in there is often geared towards actionable change in the clinic, which is what were are typically looking for as practitioners. So, for me, I like the structures where these articles go on the top of hierarchy.

Ultimately, I found this pyramid, which seems to originate from the University of Virginia Health Sciences Library, to match up with the evidence I was seeing most regularly.

For the studies, we’ve looked at, I’ve found that cross-sectional studies, animal research, article synthesis and expert opinions are not common in influential therapy-related articles, thus I have left them off this OT-directed pyramid. I actually ended up adding back in the category of mechanistic study, as this was a category we were encountering in the research.

Ultimately, we came up with this categorization:

This has given us a pyramid to categorize the studies we are looking at, based on the intent of the article. As a journal club, it is not within our purview to categorize the overall level of current research available or make a formal criticism of the execution of the study.

If you would like to see our pyramid in action, please join us at the OT Potential Club.

What about qualitative evidence?

You may notice that the evidence pyramids covered so far include only quantitative study designs. Qualitative research designs like ethnography, phenomenology, and grounded theory design are on the rise in health literature, and their findings can provide rich insights into the lives and experiences of the people and communities we work with.

But the flexible nature of qualitative study designs and wide diversity of methods makes it trickier to assess the quality of qualitative findings – and to determine how they should inform

OT practice.

It is worth noting that filtered qualitative information (systematic reviews and analyses) are becoming more popular in the literature, but even these reviewers struggle to define clear criteria for assessing the strength of qualitative studies. Most qualitative research is unfiltered and requires careful analysis.

Evaluating Qualitative Evidence

There is much debate about how qualitative evidence can and should be evaluated, or if the type of knowledge gained through these studies can really be judged at all. Stories are captured and used very differently than statistics and they cannot be measured by the same standards of validity and reliability.

A number of models and checklists have been proposed for assessing whether a qualitative study is strong or poor in its design and execution, but gold standard criteria have yet to rise to the top.

Here we present two approaches: a hierarchical model and a checklist of questions for assessing the strength of qualitative study design and execution. Know that no one set of criteria can perfectly capture all the nuances of rigor in qualitative research, but these approaches can offer a great starting place for feeling out the strength of a study and its relevance to your practice and clients.

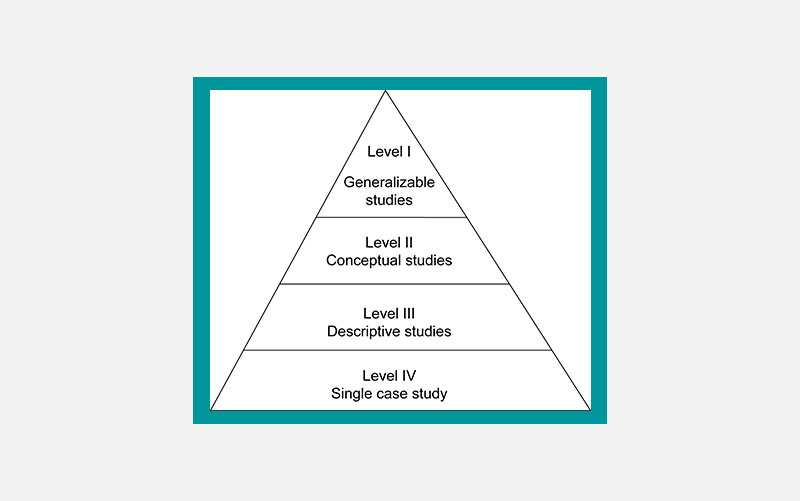

Daly et al. (2007) offers us this hierarchy for assessing the strength of qualitative studies, with the ideal studies being those which are most generalizable to other settings.

Level 1 (Generalizable Studies)

The ideal qualitative research for informing your evidence base is one which builds off existing literature and theoretical frameworks, provides detailed and comprehensive descriptions of data collection and analysis, and offers clear implications for practice and policy. Generalizable studies should clearly report on sampling saturation and diversity, as well as detail the study’s relevance to other populations and settings.

Level 2 (Conceptual Studies)

Existing theoretical concepts (like stigma, cultural identity, or gender differences) guide conceptual studies, and participants in these studies are selected to understand the concept through their lens. The goal of conceptual studies is to develop an overall account of the relationship between participants and the

Level 3 (Descriptive Studies)

Descriptive studies, as their name suggests, describe rather than explain participant experiences and views, typically through direct quotes. This study type is often seen in mixed methodology research to give additional context and richness to quantitative data.

Level 4 (Single Case Study)

The ‘lowest’ level of qualitative evidence comes from studies that include a small group or single subject. Case studies can shed light on previously unexplored or underrepresented experiences in healthcare, but their very small sample sizes limit the generalizability of these findings to broader populations. These are often used as starting points for generating future research questions rather than providing direct evidence for practice or

policy.

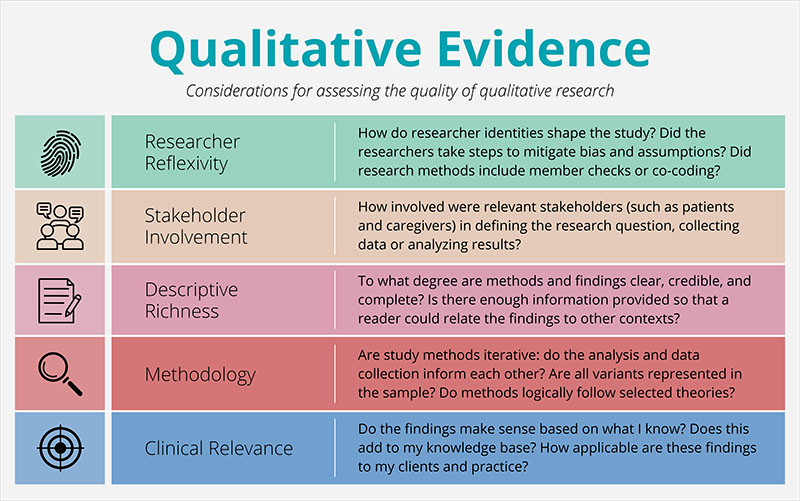

Things to look for (and to look out for) in qualitative studies

In qualitative research, rigor is less about the type of study design and more about the researchers’ transparency, descriptiveness, and adherence to the methodology.

It can be tempting to skip straight to the quotes in a qualitative study – quotes are compelling, moving, and often the most interesting part of qualitative research! But quotes alone do little to inform practice unless they are contextualized within the study by comprehensive and transparent descriptions.

Quality checklists are another imperfect yet useful way of assessing qualitative studies without hierarchy. The table below is synthesized from articles from 2020, 2007, and 2000. From these articles, here are five important considerations to look for when assessing a qualitative study:

In the video below, you can see an example of how this checklist and the hierachy above can be used by OT practitioners to evaluate qualitative research:

Conclusion

We hope that this review of the levels of evidence has empowered you to let go of the assumption that research hierarchies are intimidating and immutable. Rather, they are meant to be a helpful tool to assist in your clinical reasoning.

These research hierarchies attempt to provide a common language and some starting points for the most important step: analyzing and discussing how research can best serve your patients.

Lastly, if you are interested in OT-related research, we hope you consider joining us in the OT Potential Club!

About the Authors

Bryden Carlson-Giving, OTD, OTR/L, is a doctoral student and neurodivergent therapist with clinical interests in neurodiversity-affirming approaches, top-down assessment and treatment strategies, and ethical evidence-based practice.

Sarah Lyon, OTR/L, is the founder of The OT Potential Club, an evidence based practice platform for occupational therapy practitioners and students.

Alana Woolley is an OTD student completing her doctoral capstone with OT Potential, developing EBP and knowledge translation tools for the everyday practitioner. Her clinical interests include pediatrics, mental health, and identity-affirming care.

References

AOTA APP Levels and Strength of Evidence | AOTA. (2024).

Busetto, L., Wick, W., & Gumbinger, C. (2020). How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurological Research and Practice, 2(1), 14.

Daly, J., Willis, K., Small, R., Green, J., Welch, N., Kealy, M., & Hughes, E. (2007). A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(1), 43–49.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 320(7226), 50–52.

6 replies on “Levels of Evidence in OT”

This is super helpful, Sarah and Bryden. I am working hard to integrate EBP into the courses I write and this will help me to determine what sources to include. Thank you!

You are doing such great work, Gwen! Keep it up! Evidence is far from perfect, but should definitely be part of the equation in our decision making and teaching.

Thanks Sarah for making Evidence Based Practice so clear.

Hello!

Thank you for this very informative post! I am currently a Fieldwork Level 2 student who is integrating EBP as part of my final project. You refer to Kielhofner & Taylor, 2017 when you first describe the categorization of evidence. Do you have a full reference available for that in-text citation? Thank you.

Oh man! How did we miss that? Here is the full title: "Kielhofner’s Research in Occupational Therapy: Methods of Inquiry for Enhancing Practice 2nd Edition." I will get that added to the citation list! Thanks for catching that!

Thank you for this insightful exploration into the levels of evidence in occupational therapy! As a practitioner, understanding these distinctions is crucial for delivering effective, evidence-based care. Your article clarifies the complexities of EBP beautifully. Looking forward to more enriching content like this!