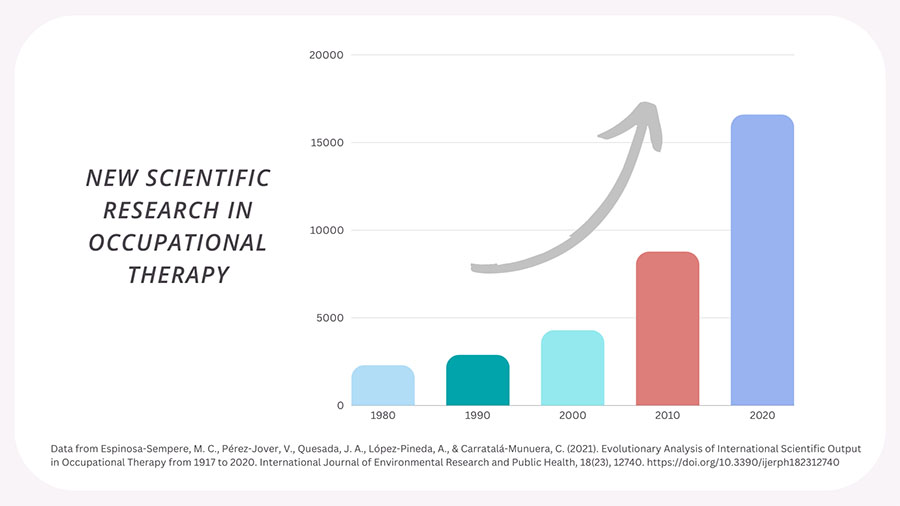

10 years ago, our problem in OT was:

We need more research!

Since then, the amount of research has increased so much, that now our problem is:

How do we get this research into practice?

The answer is knowledge translation. In this toolkit, we’ll walk you through practical steps occupational therapy practitioners can take to translate new knowledge into practice!

Here’s what you’ll find:

Preamble: Intro to Knowledge Translation (KT)

- Access Knowledge

- Links to Reputable Sources

- The Process of Inquiry

- AI Research Tools

- Accessing Non-Research Information

- Apply Knowledge

- Ways to Apply Evidence to Practice

- Recommendations for OT Managers and Leaders

- Share Knowledge

- The Importance of Patient Education

- Sharing with your Clients and Community

- Sharing with your Community of Practice

- Sharing with the Research Community

Introduction to Knowledge Translation

There is more occupational therapy research at our fingertips than ever before. In fact, OT-related research has increased exponentially in the past few decades—with the past ten years seeing nearly double the research output compared to the number of studies published in the decade prior.

Despite these advancements, new evidence won’t benefit OT clients if it isn’t effectively applied and communicated. This is where knowledge translation comes in.

Knowledge translation is a highly complex process—but taking action doesn’t need to be complicated! In this article, you will find information and resources to access synthesized knowledge, utilize knowledge in clinical practice, and effectively communicate knowledge with your clients and community.

Knowledge Translation Definition

Knowledge translation (KT) is an essential part of evidence-informed practice. And, everyday OT practitioners play a huge role. So what is knowledge translation, and why aren’t we talking about it more?

The Canadian Institute of Health Research defines knowledge translation as:

“A dynamic and iterative process that includes the synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve health, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the health care system.”

The World Health Organization and the U.S. Center for Dissemination of Disability Research also follow this definition.

Simply put, knowledge translation is the driver that moves the knowledge gained from scientific research to those who ultimately use and benefit from that knowledge: practitioners, academics, policymakers, advocates, and health consumers.

Knowledge Translation and Implementation Science

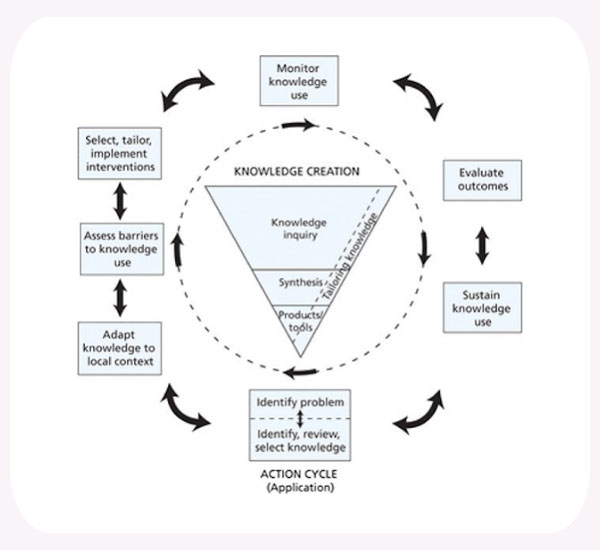

The fields of knowledge translation and implementation science have emerged in recent decades to address the dreaded 17-year research-to-practice gap. Thanks to these fields, we now have an abundance of theories, frameworks, and strategies to guide knowledge translation efforts. The most popular framework I came across in the literature was the Knowledge to Action framework (KTA).

Traditional KT frameworks like this offer a glimpse into the incredibly complex set of processes involved in bringing evidence into practice—including the need to synthesize and adapt knowledge so it can be easily utilized.

But if this model left you scratching your head and wondering how to actually do knowledge translation, you are not alone. Through my own investigation into how to improve knowledge translation in clinical settings, I found that the language and ideal application of knowledge translation research is often inconsistent and sometimes muddy, even for implementation scientists.

Let’s simplify it. The KTA framework divides the KT process into the knowledge creation cycle (i.e., asking questions and synthesizing information) and the action cycle (i.e., applying information to practice and sharing it with others).

For the everyday OT practitioner, this reflects the ways in which professionals access, apply, and share knowledge with their communities—which means you are already engaging in knowledge translation anytime you apply what you know to your practice or share knowledge with your clients!

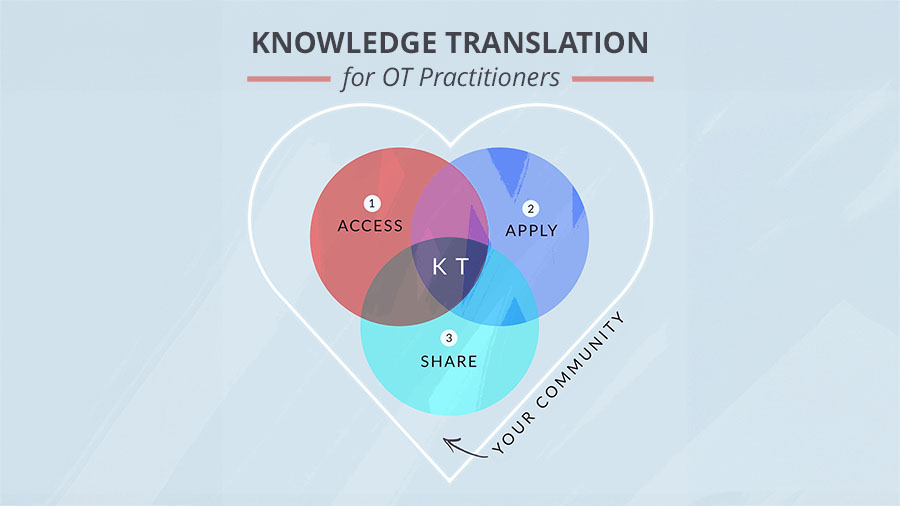

The OT Potential Club Knowledge Translation Model

Many traditional KT frameworks and models focus on the role of researchers and implementation specialists in disseminating and implementing knowledge. Here, we flip the script to center the everyday practitioner as the intersection between evidence and practice, researchers and communities.

The OT Potential Club knowledge translation model simplifies the KT process into three actionable steps:

- Access – Take in new information from a variety of sources.

- Apply – Synthesize and integrate new information into practice.

- Share – Communicate information effectively with others.

Occupational therapists straddle all of these roles, critically consuming evidence from research, our community, and our experience to inform clinical decisions—as well as extending valuable knowledge to clients to help them make informed health decisions.

This toolkit is designed to give you a broad overview of knowledge translation from the practitioner’s perspective, so you can decide where the most pressing need is in your practice. It does not reflect the full scope of the complex world of knowledge translation and implementation science. I would recommend this report from the American Institutes for Research for a broad conceptual overview of these fields.

Let’s dive in.

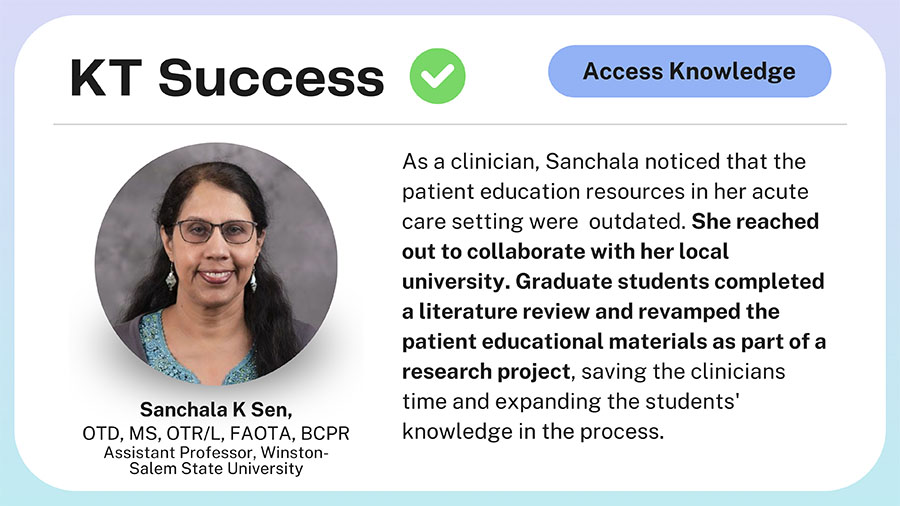

1. Access Knowledge

Effective and high-quality healthcare has to start with high-quality evidence. Occupational therapists gather evidence from a huge variety of sources to inform their practice. Thus, they need the skills to critically assess information from empirical research findings, their organizations and teams, and their clients.

Where does good evidence come from?

Let’s face it: accessing research evidence can be a struggle. We have limited time, and many resources are trapped behind paywalls. Fortunately, the majority of what you need to get going is free! Plus, there are so many new and innovative ways to engage with research evidence that can save you time and alleviate the stress of not knowing where to begin.

Of course, you can always find reliable information from credible national and international organizations like AOTA, the Cochrane Collection, the CDC, and the WHO.

And on OT Potential, you can familiarize yourself with easy options for accessing research, refresh your research appraisal skills, and get started with a helpful list of OT journals.

But what busy clinicians find the most useful is synthesized evidence—the big takeaways that really matter to clinical practice. To get you started with synthesized evidence, we compiled a collection of recent clinical practice guidelines in the OT Potential Evidence-Based Practice post. You can even synthesize scholarly research in a snap using the power of AI!

Process of Inquiry

Regardless of where your search takes you, the process of clinical knowledge inquiry can guide you in defining and answering your research questions.

1. Get Curious: It’s okay to start with a broad search tool like Google when investigating something new, but don’t stop there. As you learn more, narrow in on the population, intervention, condition, and outcome (PICO) you are curious about.

2. Define your Question: Get specific. When it comes time to refine your search in the research literature, you should have a pretty well defined and targeted research question. Specific questions will guide you toward the results that are most relevant to your client.

3. Gather your Evidence: Though necessary, research literature isn’t enough to answer clinical questions. You should also consider evidence from colleagues, courses, respected organizations, relevant blogs, and your own experience. Don’t forget to include the client if your question is about client care.

4. Appraise and Apply Evidence: Decide which evidence is suitable and integrate it into practice (more on that in a bit). Measure the outcomes of evidence application for your clients and organization. Evaluate client response to evidence.

5. Rinse and Repeat: Reflect on knowledge gaps or potential next steps in your inquiry, prioritize what is most pressing to your practice, and continue to build on your knowledge.

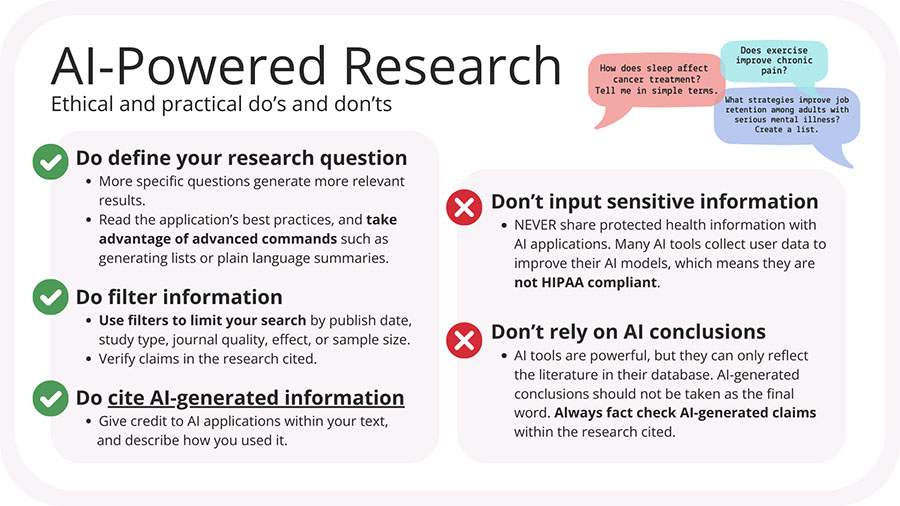

Artificial Intelligence Research Tools

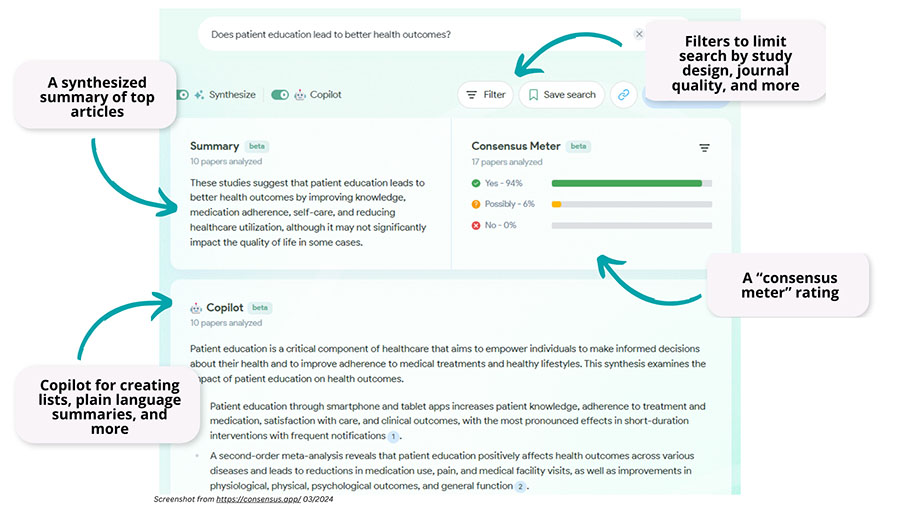

Artificial intelligence (AI) tools are rapidly advancing the ways practitioners engage with research by making it easier than ever to access filtered and actionable scientific information. By searching through open-access research articles, AI-powered literature review tools such as Elicit and SciSpace can summarize findings from an extensive database of knowledge. These AI apps do the legwork of pulling out the most important takeaways, so you can focus on the work of putting that knowledge into action.

My personal favorite AI research tool at the moment is Consensus AI. This handy synthesis tool is in the beta stage, but with some careful filtering can provide well-organized and practical results.

Consensus searches through hundreds of millions of research papers and pulls the top 10 articles to give you:

The effectiveness of any AI application depends on how you use it. Some general ethical and practical considerations for using AI-powered research tools include:

Accessing Non-research Information

Evidence-based practice involves so much more than reading and understanding empirical research. While traditional knowledge translation models focus primarily on research knowledge, the reality is that much of the clinical wisdom in OT practice is shared informally—in break rooms, during treatment, and on the internet.

Podcasts, blog posts, social media videos, graduate fieldwork and capstone experiences, and break room chat can provide insight into evidence in ways that are convenient and easy to apply to your own practice. Without the formal rigor of scientific peer review, it can sometimes be difficult to know if these sources are trustworthy for useful and reliable advice about a topic.

Some general considerations to keep in mind when assessing (and sharing!) non-scientific information include:

- Transparency – Who is sharing this information, and what is their expertise on the topic? What biases might they hold?

- References – Is it clear where this knowledge comes from? Is this knowledge based on up-to-date and accurate information?

- Reflexivity – Is the sharer open to questioning or challenging their knowledge? Does the information align with your clinical knowledge and values?

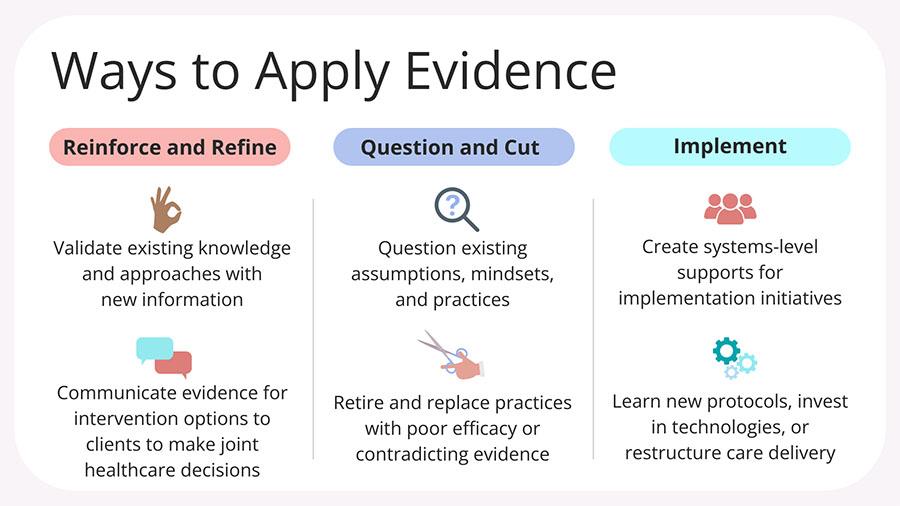

2. Apply Knowledge

Once you’ve found the best information, how can you be sure you are appropriately integrating new knowledge into evidence-based practice? There is no shortage of organizational, cultural, and personal barriers to effective EBP application. But most of the time, applying evidence to practice is actually easier than you think!

Different Ways to Apply Evidence to Practice

Some research studies provide information about highly structured interventions and protocols that require deep consideration for generalizability and feasibility in different populations and contexts. But typically, research evidence provides more general recommendations to help us validate or question what we already know.

Don’t judge a research study by its cover (or by the highly complex and intimidating intervention it discusses). With a discerning and creative eye, there are gems of knowledge to be pulled out of almost any study.

Let’s say you come across this exciting study about brain-computer interface technology for stroke recovery. But you don’t have access to BCI technology in your clinic, and you definitely don’t have time to run this intervention 5x a week with your clients…

You can still use this information to inform your evidence base by recognizing the underlying principles that led to the success of this intervention (mental practice! brain plasticity!), critically comparing those principles to your current approaches, and discussing developing treatment options with your clients.

Recommendations for OT Managers and Leaders

For managers and leaders of occupational therapy professionals, the best first step you can take toward fostering a culture of evidence-informed practice is to understand the most frequently cited barriers and facilitators of knowledge translation in clinical settings.

Luckily, this is where knowledge translation research is particularly strong. According to these studies from 2020 and 2021—as well as insight from OT Potential members—the most common KT barriers and facilitators include:

Influencing the culture of an organization can be a daunting task, but there are plenty of relatively straightforward strategies for increasing therapist motivation and capacity for engaging in EBP. Depending on your local context, many of these strategies can even be woven into existing workflows.

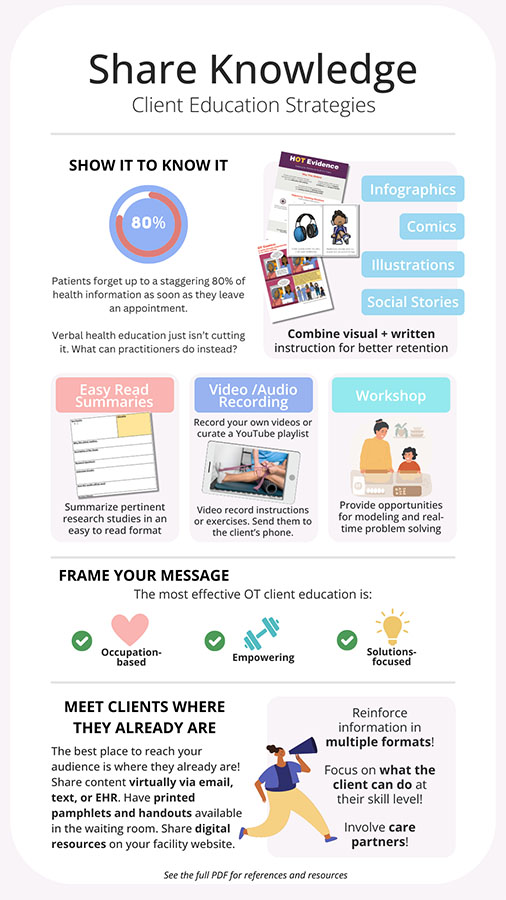

3. Share Knowledge

Sharing knowledge is the fun part! And it’s all about relationships and creativity—so it’s no surprise that OT practitioners do this part well.

The purpose of knowledge translation is to move information into the hands of those who benefit from it. So, I was surprised to find that many KT models and frameworks don’t consider health consumers as the “end users” of knowledge.

As occupational therapy professionals, we are in an ideal position to extend health information to those for whom it matters most: our clients and communities.

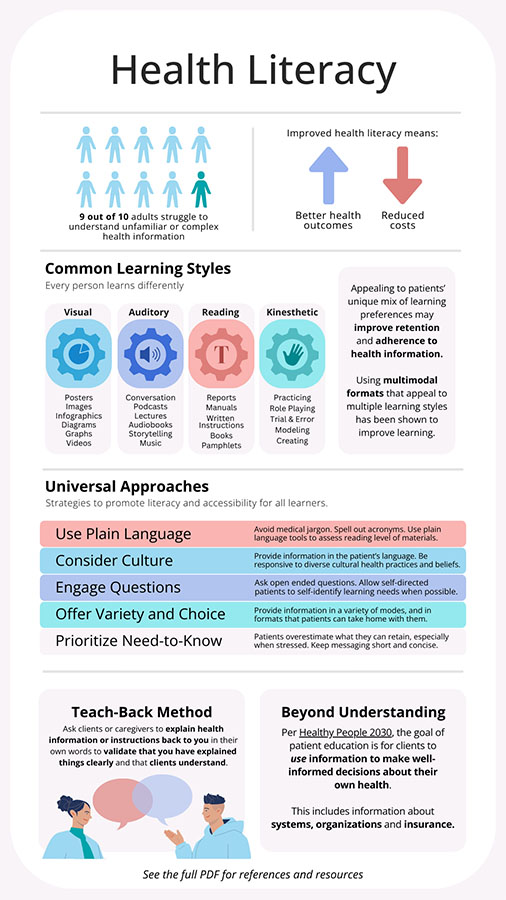

Why Patient Education Matters

Not only is patient education a fundamental part of client-centered practice, but empowered and informed patients also have significantly better health outcomes and adherence to their care plans, require fewer medical visits on average, and are more satisfied with their health care and quality of life.

These benefits have ripple effects across healthcare systems as well. Poor health literacy and non-adherence to care plans rack up billions of dollars annually in avoidable healthcare costs.

Fortunately, there is an abundance of resources and strategies for improving communication with clients. Bonus: Many of these strategies are universal and can also be applied to colleagues, community members, policymakers, and even yourself to improve learning and boost retention!

Share with your Clients and Community

The most effective health education is more than just informative – it is tailored to the learner’s needs. Whether you want to share knowledge with clients, policymakers, or your broader community, it is worth understanding how individuals best learn and retain information.

Effective Ways to Share Knowledge (the Fun Part)

Once you’ve identified how your audience learns and what information is the most important for them to know, you can move on to the fun part: sharing!

User-friendly websites like Canva make it easy to design stylish and practical educational materials for your clients. In fact, the images and infographics found in this post were all created on Canva!

Creating your own educational materials doesn’t take a degree in graphic design—but it does take time. And with so many OT professionals already creating their own resources, there’s a good chance someone else has already created something similar to what you need. Keep reading to discover a brand-new resource clinicians can use to share their resources and handouts with the OT Potential community.

Share with your Community of Practice

Knowledge translation is a team sport—one that requires testing, measuring, and reporting on evidence-in-practice to make sense of knowledge in real-world contexts. OT Potential members report that a supportive culture of evidence-based-practice in their workplaces is one of the most powerful facilitators of knowledge translation. Whether in your IRL workplace or in virtual forums and communities, supportive communities of practice are the playing ground for sharing knowledge, experiences, and resources.

OT Potential Members can share their resources here!

Share with the Research Community

The relationship between research and practice is constantly evolving. As much as there is a need to nurture evidence-informed practice to deliver the most effective therapy, there is also a need for more practice-informed evidence—research that addresses the questions that are most significant and relevant to our clients.

Conclusion

To recap, here’s what we covered:

Occupational therapy professionals are uniquely positioned to bridge the gaps between scientific research, clinical practice, and healthcare consumers.

I hope this toolkit has empowered you to see yourself as the knowledge translator you already are—and to identify some practical ways to improve your knowledge translation skills.

To help get your own wheels turning, here are my personal takeaways from creating this toolkit:

This toolkit is intended to grow and change along with our understanding of what actually works for everyday OT practitioners. And you can help us continually improve.

Share your own favorite knowledge translation tools, strategies, and success stories in the comments!

Additional Resources:

Eljiz, K., Greenfield, D., Hogden, A., Taylor, R., Siddiqui, N., Agaliotis, M., & Milosavljevic, M. (2020). Improving knowledge translation for increased engagement and impact in healthcare. BMJ open quality, 9(3), e000983. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2020-000983

Kelly, W., Meyer, H. S., & Blackstock, F. (2020). Best Practice in Educational Design for Patient Learning. In M. L. Moy, F. Blackstock, & L. Nici (Eds.), Enhancing Patient Engagement in Pulmonary Healthcare: The Art and Science (pp. 41–55). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44889-9_4

Paterick, T. E., Patel, N., Tajik, A. J., & Chandrasekaran, K. (2017). Improving health outcomes through patient education and partnerships with patients. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center), 30(1), 112–113. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5242136/

Mbanda, N., Dada, S., Bastable, K., Ingalill, G. B., & Ralf W, S. (2021). A scoping review of the use of visual aids in health education materials for persons with low-literacy levels. Patient education and counseling, 104(5), 998–1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.11.034

Simonsmeier, B. A., Flaig, M., Simacek, T., & Schneider, M. (2022). What sixty years of research says about the effectiveness of patient education on health: a second order meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 16(3), 450–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2021.1967184

Timmers, T., Janssen, L., Kool, R. B., & Kremer, J. A. (2020). Educating Patients by Providing Timely Information Using Smartphone and Tablet Apps: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(4), e17342. https://doi.org/10.2196/17342The Ultimate Guide for Patient Education Materials — Etactics. (2021). Etactics | Revenue Cycle Software. https://etactics.com/blog/patient-education-materials

One reply on “Knowledge Translation for OT Practitioners”

Alana, thanks so much!!

You’ve integrated insightful resources, your compassion is palpable, and you’ve made Knowledge Translation and it’s components accessible and understandable. Incredible!

I’m working on and alongside a couple of KT research endeavors and I curious if you’d be open to some questions??

Thanks again for your work!

Kindly,

Dustin Hogan